Episode 9 – Udawalawa National Park

An Unexpected Meeting

In my lengthy career in the Wildlife service spanning more than two decades, I have served across many divisions throughout the country,spanningregions in Thanamalwila, Handapanagala, Nuwara-Eliya, Adam’s Peak, etc. I started as a Wildlife Guard in 1996, and later was promoted to the rank of Ranger.In 2016, I received a placement toUdawalawe National Park, which is one of Sri Lanka’s distinguished National Parks and the closest one from Sri Lanka’s prominent metropolis, Colombo.

Udawalawe National Park is renowned for its rich biodiversity.With large herds of roamingelephants,throngs of deer frolickingaround and about, lively birds sporting vibrant plumage obviouseverywhere you look, and even the lucky glimpse of a jungle cat going about its business – Udawalaweisan enticing destination for locals and tourists alike. Even for thoseintricately familiar with the park and all its residents, however, there remains a creature which bears the undisputed title for being the most elusive of them all – the Sri Lankan leopard.

Every New Year’s Eve, I head home and return the following New Year’s Day, but on December 31st, 2016, I decidedto stay later than usual courtesy of anunfinished workload.When I was finally departing for home, it was during the closing hours – when all the visitors leave the premises. I heard the familiar rumble of a 4×4 engine behind me. I turned to see if I could hitch a ride to town, but it was already full.Suddenly, the cheerful faces of the crowd turned pale in sheer horror,and some started to frantically shout and gesture towards me. I turned around to check the reason for this sudden douse in spirit and froze.

A leopard, so close that its distinct, rank odor filled my nostrils. So close enough, I could reach it with my foot if I leaned just a hairs-length forward, not that I was in a state of mind to test this theory. So dreadfully close with its fierce eyes narrowed and its form crouched in position ready to attack the moment it sensed I was a threat. And there I stood, unblinking and unflinching, not because of some sudden dose of courage but because I was too terror-stricken to think or recall even the basic of human motor functions. It glared at me, daring me to move, to display even the slightest hint of hostility. Fortunately, I didn’t.And then, in a blink, it turned and disappeared into the dense thicket of the forest.I exhaled for probably the longest time I’ve done so in my entire life. Relief flooded in with each fresh gulp of oxygen. Feeling returned to my numb, rooted legs so fast that an unwary observer would think I had been electrocuted due to the sudden wobbling and shaking. In blessed relief I turned around. And froze again.

A leopard! Yes, another one. A large, dangerous feline standing so close that I am sure I could count thespots pockmarking its face.The perfect mirrored facsimile of its predecessor braced and ready topounce the moment it sensed danger. And all the bloodpumping in my veins seemed to freeze in place, again. This time, I feared the beast would actuallybe able to hear my poor beating heart, working harder that it has ever had to, desperately trying to stimulate and revive – again – the motor function in my body which seemed to be more dead than a doorknob. I stood there, my gaze transfixed at the predator, oblivious to the world around me. And then, without a moment’s hesitation, it turned and disappeared into the same path as done by its precedingbrethren. Feeling returned to me so fast and in such force,it threatened to toppleme over. As I stood, holding both shaky kneeswith my cold, numb handsand salivating every fresh gulp of air my lungs demanded, I noticed the return of chatter with sighs of relief. It was thenthat my thoughts returned to the crowd.

Maybe they had been scared to shout throughout the whole unexpected encounter, or maybe they did shout but I was too scared to notice, that I had blocked them out. Nevertheless, I thanked them for their timely warning, and we said our goodbyes. A fewminutes later, I was able to gather my thoughts properly to logically assess the whole situation. Despite the Sri Lankanleopard’sreputation of a ruthless predator, I remember that leopard attacks on humans were incredibly and extremely rare. Not that this fragment of information would have been any help to me during the whole ordeal, but for what it’s worth, both the patrons and I had an interesting tale to tell. We had seen not one, but two leopards in the wild!

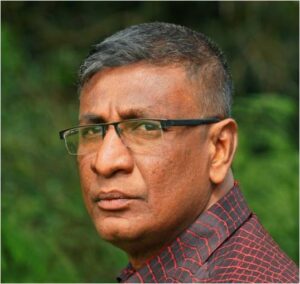

Mr. Anil Chandra Vithanage

Anil Chandra Vithanage was born in Avissawella. He received his primary education from Thalduwa Buddhist College, Kegalle and passed A / L at Eheliyagoda Central College. He has completed a course in Civil Engineering and is engaged in a related field. Due to his passion for a job in the Department of Wildlife, he joined the National Zoological Gardens Department and joined the Young Zoologists Association. It is through this that he gained his basic knowledge of animals. He also gained a broader knowledge of snakes. During this time, he also studied a librarian course.

Anil Vithanage was fortunate enough to join the Wildlife Department on 24.06.1996 as a Wildlife Ranger, fulfilling his desire. He had the opportunity to work at the Handapanagala site for the first time and has also served in difficult areas such as Thanamalwila and Nuwara Eliya.

Mr. Vithanage, who is more interested in exploration and research, has conducted research on dwarf elephants, white sambhur and endemic birds at the Siripada site and has also contributed to confirming the blue color of the blue Ceylon olive plant.

He was promoted from the Samanala site to the Rantambe Sanctuary. There he took measures to prevent spreading of a very invasive plant called Polonia samantose which is being followed by the Department of Wildlife to prevent it from spreading by the private sector. The case is not over yet. As a result, the plant was prevented from entering the Knuckles Reserve.

Mr. Vithanage’s wife is a teacher and their family consists of a daughter and a son. Mr. Vithanage says that his children also love the forest and wildlife as he. They are currently residing in Maduluwa, Avissawella.

Udawalawe National Park

Udawalawe National Park, which bordering the Moneragala District of the Uva Province and the Ratnapura District of the Sabaragamuwa Province was declared on 30 June 1972 under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance for the protection of wildlife lost due to the Walawe River Development Scheme and for the protection of the watershed area of the Udawalawe Reservoir.

Among the National Parks located in Sri Lanka, it is a National Park located closer to Colombo and has a total area of 30821 hectares. Isolated mountains can be observed in the predominantly plain area. The Kaltota Range located in the North and the Diyawinna Ella enhance the natural beauty of the Park.

Entrance of the Udawalawe NP

The land where Udawalawe National Park is located has a long history. The beautiful Kaltota area in the Walawa valley is famous as a village (Gamvaraya) gifted to Neelamaha Yodhaya (a leading person from King’s army) by King Gajaba. There is also evidence that the Neelamaha Yodhaya engaged in agriculture in this area. Seenuggala, Muwanpelessa in the Udawalawe National Park were prosperous villages in the past. Ancient stone pillars and ruins found in the Veheramankada and Veheragolla areas confirm the existence of settlements in that area.

The Udawalawe Reservoir was built by blocking the Walawe River, one of the main rivers in Sri Lanka that flows through the park. Spread over an area of 1,155 sq km, the Walawe River originates in the Samanala area, joins many other streams and flows through the Udawalawe National Park, creating a unique ecosystem for its wildlife. In addition to the Udawalawe Reservoir, the National Park also provided habitat for wildlife displaced during the creation of the Chandrika Wewa, Samanala Wewa and the Mau Ara Reservoir which built under the Walawe River Development Project.

Situated in arid and sub-climatic zones, the park receives rainfall mainly from the Southeast monsoon. The annual rainfall is approximately 1524 mm and the average temperature is around 32 degrees Celsius. The western part of the park belongs to the intermediate zone, and receives relatively high rainfall. The border zone near Ratnapura shows the wet zone features while the border belonging to Moranagala District shows the dry zone features. There is a short dry season in February and March of the year, and sometimes this dry weather lasts from mid-May to late September, by September, inter-monsoons receive rainfall. The Northeast monsoon winds bring rain from November to mid-January. In addition, convection rains are received from April to May. Wind speeds from May to July vary from 5.9 km / h to 6.3 km / h. The highest winds are seen in June.

Udawalawe National Park has primary and secondary forests as well as open grasslands, savanna grasslands, shrub forests and teak plantations. Prior to its declaration as a National Park, the area was subjected to clearing of forests. For this reason, many open lawns can be seen in the park today.

Among the existing plant species in the garden, tall plants such as satin, halmilla, ebony, kolan, milla, kone, kunumella etc. can be seen and Nelli and Bulu are found as medicinal plants. Kumbuk and Mandora are predominant plants on both sides of the Walawe River. Grasses such as Mana, Iluk, Pohon and Damaniya are also found in grasslands. Invasive plants such as Lantana and Kuratiya, which are ufavourable for wildlife, are a threat to the park.

The Udawalawe Reservoir and the Walawe River, which provide water to wildlife throughout the year and due to the abundance of food in the ecosystem, the Udawalawe National Park is home to approximately 250 Asian elephants and many other species.

Large mammals found in the park including elk, spotted deer, wild boar, wild buffalo, and small mammals such as golden jackales, toddy cat, torque monkey, and rabbits. Cat family animals including leopards, rusty cat, fishing cat and bears are also found in the park. But the chances of seeing bears are very rare as there are a small number of bears there. Five species of rats, 30 species of snakes, 03 species of deer and about 50 species of butterflies are also found in the park. Among the reptile species are several species of lizards and the marsh crocodile, water monitor and iguana.

Among the species of birds found in the park are the endemic birds of Sri Lanka such as the spur fowl, the red-faced cuckoo, the gray horn bill, the jungle fowl, the Malabar pied hornbill, the tambaseruwa, the golden breasted pigeon and the changeable hawk eagle. Aquatic birds such as seagulls are common in the Udawalawe and Maura reservoirs.

The distance from Colombo to the entrance of this national park is about 165 Km. The easiest way to reach the park from Colombo is to take the Thanamalwila road from Colombo via Ratnapura Pelmadulla to the left of the Thimbolketiya junction on the Pelmadulla – Embilipitiya road. The entrance to the park is located near the 7th km post on the Thanamalwila road.

Another tourist attraction of the Udawalawe National Park is “Elephant Transit Home”. The “Elephant Transit Home” was established in 1986 near the Udawalawe National Park as a place to take care of the baby elephants until they mature enough to live alone in the jungle, rather than bringing in baby elephants that escape from the herd or die in the wild. Playing baby elephants growing up in the “Elephant Transit Home” in front of the Udawalawe Reservoir will get attracted anyone who visits here.

Baby elephants in the Elephant Transit Home

Visitors to Udawalawe National Park can obtain tickets at the entrance office and there is an improved road network in the park for the convenience of visitors. Camps have been set up at Pransadara, Elephant Pass, Pilimaddara, Ranagala, Alikatupelessa and Hadagiriya for tourists who wish to spend the night in a campground and experience the wonders of the jungle. These campgrounds are located in a unique area that allows visitors to enjoy the maximum of wildlife and the unique experience of living in the jungle. Tourist lodges with all facilities have been constructed at Thimbiriyagasmankada, Weheragolla, Seenuggala, Gonaviddagala and Pokunutenna areas.

List of animals in the Udawalawa document

Sinhala name | Tamil name | English name | Scientific name |

අලියා | யானை | Asian elephant | Elephas maximus |

ගෝනා | மரை | Sambar | Rusa unicolor |

තිත් මුවා | புள்ளி மான் | Spotted deer | Axis axis ceylonensis |

වල් ඌරා | காட்டுப் பன்றி | Wild Boar | Sus scrofa |

වල් මී හරකා | காட்டெருமை | Water buffalo | Bubalus bubalis |

හිවලා | நரி | Golden jackal | Canis aureus |

කලවැද්දා | ஆசிய மரநாய் | Toddy cat | Paradoxurus hermaphroditus |

රිලවා | சிறு குரங்கு | Toque Macaque | Macaca sinica |

හාවා | இந்திய குழி முயல் | Indian hare | Lepus nigricollis |

දිවියා | சிறுத்தை | Leopard | Panthera pardus kotiya |

කොළ දිවියා | துரும்பன் பூனை | Rusty- spotted cat | Felis rubginosa |

හඳුන් දිවියා | மீன்பிடிப் பூனை | Fishing Cat | Prionailurus viverrinus |

වලහා | தேன்கரடி | Sri lankaSloth bear | Melurus ursinus |

වලි කුකුළා | இலங்கைக் காட்டுக் கோழி | Sri lankajunglefowl | Gallus lafayettii |

හබන් කුකුළා | சின்னக் காட்டுக்கோழி | srilankaSpurfowl | Galloperdix bicalcarata |

රතු මුහුණැති මල් කොහා | செம்முகப் பூங்குயில் | Red faced malkoha | Phaenicophaeus pyrrhocephalus |

අළු කෑදැත්තා | இலங்கை சாம்பல் இருவாய்ச்சி | Sri lanka Grey Hornbill | Ocyceros gingalensis |

Sinhala name | Tamil name | English name | Scientific name |

පොරෝ දෑකෑත්තා | மலபார் கறுப்பு வெள்ளை இருவாய்ச்சி | Malabar pied horn bill | Anthracoceros coronatus |

තඹසේරුවා | சிறிய சீழ்க்கைச்சிரவி | Lesser whistling duck | Dendrocygna javanica |

ළය රන් බට ගොයා | செம்மஞ்சள் மார்புடைய பச்சைப்புறா | orange breastedgreen pigeon | Treron bicinctus |

පෙරළි කොණ්ඩකුස්සා | குடுமிப் பருந்து | Changeable hawk eagle | Nisaetus cirrhatus |

දියකාවා | சின்ன நீர்க்காகம் | Little Cormorant | Phalacrocorax niger |

හැල කිඹුලා | சதுப்பு முதலை | Mugger crocodile | Crocodylus palustris |

කබරගොයා | நீர் உடும்பு | Asian water monitor | Varanus salvator |

තලගොයා | இந்திய உடும்பு | Land monitor lizard | Varanus bengalensis |

List of trees in the Udawalawa document

Sinhala Names | Tamil Names | English Names | Botanical Name |

බුරුත | முதிரை | Satinwood | Chloroxylon swietenia |

හල්මිල්ල | சாவண்டலை மரம் | Halmilla | Berrya cordifolia |

කළුවර | கருங்காலி | ebony | Diospyros ebenum |

කොලං | மஞ்சக்கடம்பு | kolon | Haldina cordifolia |

මිල්ල | காட்டு நொச்சி | Milla | Vitex altissimia |

කෝන් | பூக்கம் | Kon | Schleichera oleosa |

කුණුමැල්ල | கரிமரம் | Kunumella | Diospyros ovalifolia |

නෙල්ලි | நெல்லி | Nelli | Phyllanthus emblica |

බුළු | தான்றி | Bulu | Terminalia bellirica |

කුඹුක් | வெண்மருது | kumbuk | Terminalia arjuna |

මැන්ඩෝරා | எருக்கலை | Mendora | Hopea cordifolia |

මාන | மானா | Mana | Cymbopogon confertiflorum |

ඉලුක් | தர்ப்பைப் புல் | Illuk | Imperata cylindrica |

පොහොන් | நேப்பியர்ப்புல் | Pohon | Pennisetum polystachion |

දමනීය | பலிசமரம் | Damaniya | Grewia tiliifolia |

ගදපාන | உண்ணிச் செடி | Gandapana | Lantana camara |

කුරටිය | சிறுநெல்லி | Kuratiya | Phyllanthus polyphyllus |

Editor – Dammika Malsinghe, Additional Secretary, Ministry of Wildlife and Forest Conservation (MWFC)

Article on park written by – Hasini Sarathchandra, Chief Media Officer, Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWLC)

Tamil Translations – A.R.F. Rifna, Development Officer, MWFC

English Translations (Documents) – Asoka Palihawadana, Translator, MWFC

English Interpretation (Story) – Thanuka Malsinghe

Web Designing- N.I.Gayathri, Development Officer, MWFC

Photography – Rohitha Gunawardana, DWLC

Sinhala typing & other assistance – Aruni Palapathwala, MWFC